Photographs (left to right): Flamingo, Columbus Zoo, Ohio; Vulture Grand Canyon, Tennessee; Rattlesnake, Columbus Zoo, Ohio

Wampum Belt Archive

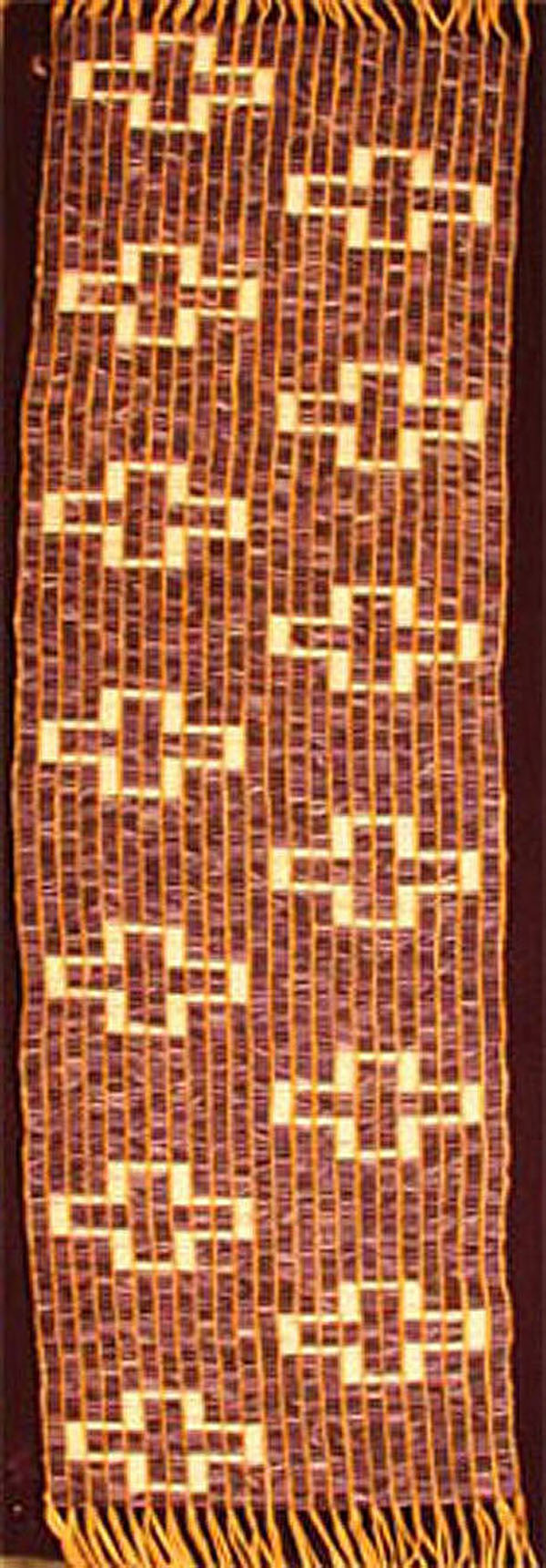

King Henry - Mohawk

Reproduction (L): R. D. Hamell Dec. 23 2012

Painting (R) circa 1710

Original Size: |

? |

Reproduction: |

Beaded length: 34.0 inches. Width: 10.5 inches. Total length Mw/fringe: 49.5 inches. |

Beads: |

Rows: 185 by 23 beads wide. Total: 4,255. |

Materials: |

Warp: leather. Weave: artificial sinew. |

Description:

The following description (in quotes) extracted from: The Hamlet of East Line New York: History in the Making: Hendrick. http://elrh.net/page21/prehistory/page8/page8.html.

The existence of the belt in unknown, but recorded in a 1710 painting of King Hendrick (Mohawk) with a wampum belt with 13 crosses that was given to Queen Anne.

"Mahican by birth (between 1680 and 1690), Hendrick (this is the form of the name most often seen in English-language sources; he was also known as Tee Yee Neen Ho Ga Row, Teoniahigarawe, Tiyanoga, White Head, Hendrick Peters, and King Hendrick) advanced to leadership among the Mohawks after his adoption into the Wolf clan. He was educated at the English Stockbridge School in Massachusetts. When Thoyanoguen became a christian he was given the name 'King Henry'. He was an advocate for native peoples rights and his moral convictions was directed against the destructive power of alcohol.

He is notable in history chiefly for his undeviating support of New York and the British crown against New France. While still a boy, he adopted Protestant Christianity, and rejected the solicitations of Jesuit missionaries.

Hendrick became prominent in 1710 as one of the so-called four kings taken to London by Colonel Francis Nicholson and Peter Schuyler who hoped that a visit by pro-British Indians would generate support for an English invasion of French Canada. The Indians were the sensation of fashionable society. Dressed in formal costume, they were presented to Queen Anne and had their portraits painted. (On a second visit to England in 1740, Hendrick was received and patronized by King George II.) The queen donated a silver communion service for a Mohawk chapel at Fort Hunter, near the predominantly Protestant Mohawk town of Tiononderoge, and the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel sent a missionary. But various factors prevented the projected invasion from taking place. Among other problems, Hendrick's Mohawk warriors were double-crossed by the Onondaga chief Teganissorens, who kept French authorities well informed of the English military's every mishap. Not for the first or last time, the Mohawks and the Onondagas pursued different policies in the course of their rivalry with each other.

Hendrick rose to special authority after the appointment of the merchant William Johnson as New York's agent in charge of Indian affairs. The chief's violently anti-French attitude fitted Johnson's policies as well. The pair seduced the Mohawks into a disastrous campaign against Montreal in 1747. Other Iroquois nations, following the Onondagas' lead, refused to join this ill-advised raid, which lost heavily when ambushed by the French and their Indian allies. Johnson resigned his provincial post in 1750, but he continued to profit from trade, and he maintained close ties with leading Mohawk families, including Hendrick's.

With Johnson out of office, the Mohawks became alienated from the policies and personnel of New York's Indian-affairs office. Commissioners in Albany made the critical decisions, and they were more concerned with acquiring Mohawk lands than with establishing friendly relations with Indian people. (Johnson himself picked up millions of acres of Indian territory, but his methods were less crude than the commissioners', and he respected the property of his Mohawk neighbors.)

In 1753, Hendrick led an angry delegation to announce at Albany that the Covenant Chain alliance, linking the colony to its Iroquois allies, had been broken. His declaration made a serious impression on the Lords of Trade and Plantations in London, who ordered a new interprovincial treaty in the Crown's own name to redress Hendrick's grievances and renew the alliance. This new agreement took place at the Albany Congress of 1754.

Virginia stayed away, and New York's governor, James De Lancey, was able to seize control of the congress for his own purposes. The Crown's interests were forgotten. In this contentious and unsettled atmosphere, Hendrick took the opportunity to impress the colonial delegates by flaunting Mohawk leadership of the Iroquois League and denigrating the Onondagas.

The Albany congress's much-touted scheme of interprovincial unity proposed by Benjamin Franklin was approved by no colony and not even considered by the Crown. The most substantial victors of the congress were William Johnson, who emerged as the Crown's direct agent in Iroquois affairs, and Johnson's old ally, Hendrick, now the dominant chief in the Iroquois League.

Much of the Albany congress's real business took place "in the bushes"-separately from the formal sessions. Pennsylvania's Conrad Weiser and Connecticut's John H. Lydius persuaded an assortment of Iroquois chiefs into signing deeds for lands in dispute between the two colonies. With full knowledge that these procedures violated Iroquois custom, and in association with signatories who had no right or authority, Hendrick signed both deeds. His political motive is not evident. He seems to have been among the men described by Weiser as "greedy for money." In due course, the lands thus deeded became the scene of the Pennamite Wars between Pennsylvania and Connecticut in the Wyoming Valley of the Susquehanna River.

In 1755, William Johnson was commissioned to campaign against the French outpost of Fort St.-Frédéric at Crown Point on Lake George. As before, Hendrick recruited a Mohawk contingent and led them personally into battle. He was always renowned for personal bravery, and he had gained a self-conception of overpowering self-importance. "We are the six confederate Indian nations," he proclaimed, "the Heads and Superiors of all Indian nations of the Continent of America." However, the Lake George battle (1755) became greatly confused, and Hendrick had grown old and fat. When his horse was killed under him, he was unable to flee and was himself killed."

Reference:

The Hamlet of East Line New York: History in the Making: Hendrick. http://elrh.net/page21/prehistory/page8/page8.html.

Hendrick Painting: http://www.mccord-museum.qc.ca

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|